The Intracoastal Waterway and the Great Loop

While Noonsite predominantly covers only coastal ports, we’ve come to realise via feedback from international cruisers that there is little information out there regarding the ICW & Great Loop specifically for international visitors to the USA. Therefore we have put this report together as an introductory guide and we welcome any feedback from cruisers who have done any or all of these routes, especially as an international cruiser. Please use the comment function via the speech bubble icon to submit updates.

Published 7 years ago, updated 3 weeks ago

Circular Route from Florida via the Great Lakes to Florida

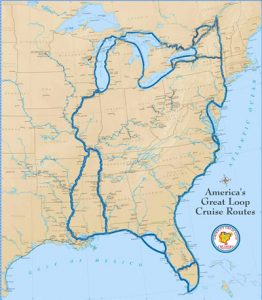

The Intracoastal Waterway surrounds the entire eastern and southern seaboards of the United States. Combined with major inland rivers and canals, it is possible to take a circular route from Florida to the Great Lakes and back to Florida, circumnavigating the eastern half of the United States entirely by water: this is known as the Great Loop.

In reference to many of the rules and regulations that are discussed here, we at Noonsite make sure to list all of the possible rules and regulations that may be encountered whilst cruising; however, enforcement may vary. (For more about this, see the comment from a cruiser below.)

Intracoastal Waterway (ICW)

The Intracoastal Waterway (commonly referred to as the ICW) is an intricate, well-established, well-charted system of waterways that allow a cruiser to drive a boat all the way from Brownsville, Texas (at the Mexico-US border) to Boston, Massachusetts, almost without ever spending much time in open water. There are only a few places that the ICW does not connect and these areas require an offshore jaunt.

The ICW is entirely separate from the sea, but it runs along the coast sometimes only a few hundred meters inland. Most of the ICW is created by linking the bays and inshore areas behind barrier islands with rivers and canals. Where there was no barrier island or natural river, the canals were cut by brute force, dynamite, and earthmoving equipment. Where the water was too shallow, an army of dredges pumped it all out to a standard depth.

The official directive is that the ICW is maintained to dredged depths of nine to twelve feet, though in reality there are some areas that silt and shoal too rapidly for the US Army Corps of Engineers to maintain. Also, the ICW is a federal project and requires government funding that is sadly lacking at this time.

There are two primary sections of the Intracoastal Waterway. The eastern section is known as the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (AICW) and runs from Boston to South Florida. The southern and Gulf Coast section is known as the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (GICW) and it runs from Brownsville, Texas, (at the Mexican border) to Carrabelle, Florida. There is an inland section from Stuart, Florida, to Fort Myers, Florida, known as the Okeechobee Waterway: it is a direct cut across the middle of the state. This route is not as common for sailing vessels with tall masts or deep draughts, but cruising yachts regularly skip the Florida Keys and open water by bisecting the state.

The Great Loop

The Great Loop is a well-established cruising route that circumnavigates the entire eastern seaboard of the United States. The traditional route is approximately 4800 miles long; but, depending on the route and how many detours are taken, the entire trip can extend to more than 8000 miles. There is no official starting point. It is most common to cruise the great loop in a counter-clockwise direction to take advantage of the natural flow of the Gulf Stream and (generally) southbound flow of the inland rivers.

There is a traditional “official” route. The Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (occasionally AICW) is used on the Atlantic coast of the United States. Cruisers occasionally will take an outside, open-water route to “jump” a section that is particularly difficult navigationally, or if speed is of the essence. Some of the most famous cruising grounds in the Western Hemisphere are along this route, particularly the Chesapeake Bay.

The Great Loop passes directly through New York City and continues up the Hudson River into the inland waterways of Upstate New York. The route to the Great Lakes can take multiple courses, but thorough research must be conducted to ensure a yacht’s draught and mast clearance can make the journey. The Great Loop continues through a portion of Canada before re-entering the United States and sailing to Chicago. The Great Lakes are inland seas: extreme weather can be just as dangerous on Lake Michigan as the North Sea.

The next leg of the journey is the major river systems of the Eastern United States. In downtown Chicago, yachts enter the Calumet River, which then joins to the Mississippi River a few miles inland. From there cruisers have access to many major cities such as Nashville, Memphis, Cincinnati, Huntsville, St. Louis, and everywhere in between. The Mississippi River route is becoming less popular in recent years. Most cruisers favor the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway (“Tenn-Tom”). While the Mississippi River holds a more legendary place in the mind of most adventuresome cruisers, there are far fewer facilities and, south of Memphis, there are many hundreds of miles between marinas, fuel stations, or services for cruising yachts.

The Gulf Coast section of the Great Loop exits through Mobile Bay (after the Tenn-Tom) and turns eastward again to return to Florida.

Skippers and crew who undertake the Great Loop are called “Loopers.” The accepted way to become an “official” Looper is to circumnavigate and return back to their personal starting point.

There are many known “Loopers” who live on their boats full-time and circumnavigate every year, spending Summers in the north and Winters in the south. It is not uncommon to meet someone who has circumnavigated more than twice.

The Great Loop has an official cruising association (https://www.greatloop.org/) and a club burgee to fly to indicate “Looper” status. The organization holds regular meet-ups all over the country.

The amount of time it takes to circumnavigate the Great Loop varies widely, but most cruisers try to start heading north from Florida in the Spring, spend the heat of the summer in the North, then come south through the river systems in the early Autumn when the leaves are just changing color. Done at a steady pace, it can be done in six months, though most cruisers take their time. An average of nine months circumnavigation time is typical.

Inlets

While many inlets are navigable by larger yachts, not all are. Local knowledge is strongly advised to safely transit an inlet. While the tidal range may not be significant compared to elsewhere in the world, the currents can be fierce. Three to four knots – and even as high as six knots! – is common in narrow channels and under bridges.

Thoroughly research any and all inlets prior to entry or exit. It would be prudent to avoid entering or exiting an inlet if no one on board has transited the inlet before. Night approaches to tidal inlets can be potentially hazardous, also. First-time visitors to the United States are advised to enter at a major port inlet where deep-water is easily found and navigation is not complicated.

It is worth mentioning that bridges pass over some inlets. Whilst some have adequate clearance or are lifting (bascule) bridges, some are short and do not open. Do not assume that all inlets offer equal access. Some lifting bridges over inlets will open on a schedule, which means approaching vessels will be required to wait in the tidal flow for the bridge to open.

Navigation

The ICW and other inshore waters are normally well-charted in the United States. Electronic charts are regularly updated. Crowd-sourced charts such as Navionics or CMAP are typically best. Most electronic charts include a “suggested line” which is not always the best course to follow in the real world, it is simply a guide to show the ICW route: channel markers in the real world should always be consulted for navigation.

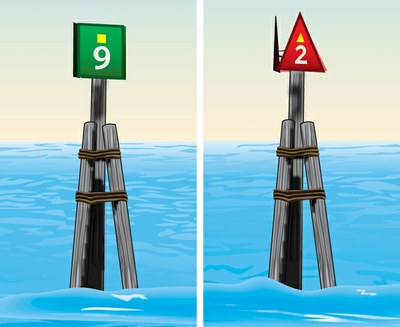

The ICW markers are usually large poles driven into the seabed. They are solid, fixed structures, often made of steel or wood like a telephone pole. They are capable of doing serious damage to yachts if struck. ICW markers are always GREEN squares and RED triangles. They will have sequential numbering, which does not indicate mileage or any other system of measurement, but they are used frequently by marinas to give directions or distance. Sometimes the number will seem to arbitrarily reset at the beginning of a new river or canal. ICW markers are able to be discerned as separate from other channel markers due to a small yellow symbol, often above the marker number. GREEN channel markers will have a small yellow square; RED channel markers will have a small yellow triangle. (Image above courtesy of Boat Delaware)

When in major inlets, shipping channels, or deep water, the fixed poles are replaced by large floating buoys. The shape of the buoy will remain the same (GREEN has a square shape and profile; RED has a conical/triangular shape and profile) but there will always be a small yellow symbol to indicate the ICW channel.

The markers follow the US Aids to Navigation System, which is occasionally different from Europe. See this website for more clarification: https://www.uscgboating.org/

ALWAYS follow markers and buoys. The ICW can be extremely shallow immediately outside the channel. Occasionally, the markers will be shifted (after storms) or there will be some need for intermediate buoys between solid markers. This is done frequently when shoaling occurs, or to indicate river bends. The intermediate markers are normally small green or red floating buoys marked with a number and letter to indicate the intermediate buoy (9A, 9B, etc).

The ICW is constantly changing. Every hurricane or torrential rain causes shifts in the sediment and shoaling at deltas. Keep a close watch on your depth sounder.

Towing

If you run aground and or otherwise are in need of a tow, there are a number of commercial organizations that exist specifically for this reason. They charge for their services per hour, but it is possible to purchase a yearly membership, which covers towing. A single towing may cost more than a year of membership.

One such organization is SeaTow. It is an official organization of captains that are available 24/7 for towing, ungrounding, disentanglements, jump starts, and emergency fuel deliveries. They are also available for some catastrophe response. SeaTow responds on VHF Channel 16.

Each SeaTow captain is local to their coverage area; therefore, many cruisers will call them on the VHF to ask about local knowledge prior to approaching inlets or before passing through a tricky navigation area. Local knowledge questions are, of course, free of charge.

Anchoring

Anchoring is permissible in the United States almost anywhere. Anchoring along the ICW is common and sometimes necessary where marinas are not available.

Many foreign skippers visiting the United States are surprised at how easy it is to anchor. The bottom of the ICW is typically receptive to the heavy spade anchors that are necessary for Caribbean and Mediterranean anchorages. Some lighter-weight anchors are easily used in heavy silt and hold easily. Remember to anchor with the tide reversal and low-water depth in mind.

Similar to elsewhere in the world, it is good manners to avoid anchoring too close to any yacht. Some small anchorages are not conducive for even two yachts to swing. Please be courteous when anchoring.

Along the ICW, there are some anchoring fields where there will be some yachts on a permanent mooring. Keep in mind that some of these yachts may not be occupied. They may be on a “hurricane mooring.”

Always anchor with a 360º visible white anchor light. It is also good practice to illuminate the deck all night if anchored in an area of low visibility (i.e., in the bend of a river or in a narrow channel).

In some states – particularly Florida – there are restrictions on anchoring too close to permanent structures. (Please visit the Florida section for more information on the local ordinances which restrict anchoring.) In Georgia, proposals are in place to restrict anchoring (June 2019). See this news item for more details.

Rules

The laws governing the ICW and the rest of the Inland Waterways of the United States are mostly the responsibility of the individual states. They tend to be fairly standard, but enforcement varies (see next section). Do thorough research prior to arrival in the area you will be cruising.

One such rule that surprises some visitors to the United States is that marine heads and overboard discharge are tightly regulated. Some laws require that you have a “lock” on your holding tank seacock. The lock can be as simple as a cable tie, but it is to prove that you are not regularly pumping out overboard and that you are attempting to comply with the law in advance.

See USA Restrictions for more details.

It is vitally important to keep your paperwork in order and get all the required permits before cruising.

Government & Law Enforcement Jurisdictions

The US Army Corps of Engineers is tasked with maintaining the ICW. The US Coast Guard patrols all coastal waters, including the Intracoastal Waterway. Also, first-time foreign visitors to the USA may not be aware that each state, county, and city have separate law enforcement entities and each may patrol the waterways depending on the individual jurisdiction of the agency: near cities, the local police may have a regular patrol; in the remote countryside, county or state police may have a waterborne presence. It is a general rule, though, that the skipper of a vessel in United States territorial waters is responsible for abiding by ANY and ALL rules, ALL posted signage, and verbal instructions from officials.

It is not uncommon for patrolling watercraft on the ICW to approach private vessels and “pull them over.” It may alarm first-time visitors to the USA because the law enforcement officers will board quickly and somewhat aggressively. This is common practice in the United States – done because some cruisers have been known to run downstairs and try to fix the problem or get rid of the evidence. But, there is no implication that any laws were broken. Most often getting pulled over in a yacht is a check for licensing, registration, insurance, head seacock closure, and (in the case of foreign nationals) immigration and customs compliance. (NOTE: It is worth mentioning that some foreign yachts do not realize that, in the United States territorial waters, the head seacock must be in the “CLOSED” position with some evidence that it is “locked.” A simple cable tie will normally do to prove that you do not frequently use the seacock. Law enforcement is known to check for head seacock closure compliance.)

Additionally, the US Coast Guard is militarized in the United States (similar to UK Border Force) and serves as a coastal protection force that also enforces immigration and customs in territorial waters. In the inshore waters or along the ICW, there are alternate agencies that are able to help in the event of an emergency. Some cities and counties have a Rescue Squad, which can assist in inshore breakdowns or health emergencies. Firefighters, forestry services, and the Department of Natural Resources all have patrolling vessels.

There are also a number of commercial enterprises that can assist in the event of emergencies, but these are for-profit and will charge for assistance. Most often, these are used for towing broken-down vessels, helping grounded yachts, or salvage. These companies are not necessarily intended to assist with emergencies but will assist (as any nearby yacht is obligated to assist in an emergency at sea).

The US Coast Guard will likely answer any MAYDAY or PAN-PAN calls near the coast and coordinate emergency response with the appropriate local agency and other nearby vessels.

Radio Etiquette and Contacting Vessels

Radio etiquette for VHF calling in the United States is exactly the same as elsewhere in the world; however, some of the channels are different. Most modern radio sets have the option to switch from “International” frequencies to “USA” frequencies. Numbers like Channel 09 and Channel 16 are the same, but more “Alpha” channels are added. It is important to switch over to these frequencies because they are commonly used in areas of increased traffic.

Most importantly, the US Coast Guard often uses VHF Channel 22A (pronounced: “twenty-two-alpha” or “two-two-alpha”) as a working channel. Some marinas on the ICW will use VHF Channel 78A or other “alpha” channels as they are designated “non-commercial port operations.”

It is paramount that you abide by all international standards for VHF radio etiquette. The US Coast Guard monitors all transmission in the coastal waters and violations are monitored and recorded. Like elsewhere in the world, “broadcasting” (calling on the VHF without an intended recipient) is illegal. Also, the use of foul language, playing music, or talking on VHF Channel 16 (except for initial contact) is also against the law.

Do not, under any circumstances, call the Coast Guard for a radio check or broadcast for a radio check without an intended recipient of the call. In the United States, this is not allowed. Never call for a radio check on VHF Channel 16. If you need a radio check, call the local SeaTow captain or a local marina on their working channel.

Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway Bridge Procedure

Nearly all fixed bridges are standardized to at least 65ft at high water – all except one bridge in the main channel of the ICW through Miami. It has only a stated 55ft clearance at the center at high water. Northbound or southbound boats with mast heights higher than about 55 ft. must leave the ICW and transit “outside” for approximately 25 miles between Government Cut and Ft. Lauderdale inlets.

Shorter bridges are all able to open, but some bridges do not operate 24 hours a day. Openings and closings are controlled at a manned control tower on each bridge. The bridge operators respond on VHF Channel 09. (Never use VHF Channel 16 to contact bridge controllers to request a bridge opening.) Standard VHF radio etiquette is expected and violators are reported to the Coast Guard.

Even if a particular bridge opening abides by a schedule, it is standard procedure for every yacht awaiting a bridge opening to contact the specific bridge BY NAME and request the opening, even if many other yachts have already done so. Make the call using proper VHF radio etiquette using the official name of the bridge and announcing the name of your yacht, as well. Bridge information is listed in all charts: the name of the bridge, air draught clearance, and opening schedule. If you are requested to spell the name of the yacht, do so with the phonetic alphabet. This is done for safety purposes to ensure all yachts in need of the opening pass through the open bridge before closing, and a record is kept of all yachts transiting the bridges.

Occasionally, wait times at bridges can be long and many vessels will be waiting on both sides.

There is no “official” etiquette for who has the right-of-way when transiting bridges, but it is customary that the boats coming downstream pass through the bridge first. Keep in mind that the tide shifts the current, and “downstream” occasionally switches. Towboats, mega-yachts, river cruise boats, and any limited-maneuverability vessels will typically notify all nearby craft of their intentions long before the bridge opens. This notification typically occurs on VHF Channel 09.

After passing through the opened bridge, it is the standard courtesy to announce to the bridge on VHF Channel 09 that your yacht is clear of the bridge. It is at this point that you sign off with an “out” call.

The ICW bridges are only obligated to open for yachts with fixed structures (i.e., masts, fixed radar arches). Antennae, satellite domes, and collapsable radar arches must be in the “down” position. Vessels that refuse to lower collapsable structures may be reported by the bridge operator to the US Coast Guard and subject to a fine.

Provisioning and Facilities

Some areas of the ICW are extremely remote and cut through long sections of the uninhabited landscape. It is also common to cruise more than 100 miles without a fuel dock. Serious cruising of the ICW or any of the United States requires careful strategy and provisioning, not to mention a yacht that is largely self-reliant. Many ICW cruising yachts make use of generators. Wind speeds are rarely strong enough to rely on a wind generator, but solar panels can be used effectively in the southern states.

Facilities along the United States coast can range from megayacht harbors with resort-style amenities to tiny fishing piers advertised as “marinas.” Most cruisers report that some of the most enjoyable experiences they ever had were a result of staying on a dock they thought their yacht would break. Water quality should be potable nearly everywhere – even in more rural areas – but electricity may not be available at smaller marinas except through a standard (household) plug.

It is possible to find “courtesy docks” in some cities. Typically, these are city quays, municipal piers, or docks attached to parks or convention centers that are meant for relatively short stays but are free to use. These courtesy docks are almost always in excellent locations, often directly downtown, and are designed to encourage boaters to visit downtown. There is usually a posted limit to how long you may stay at a courtesy dock: often a matter of 12-hours, 24-hours, or one overnight. Long stays are discouraged and may result in a fine for overstaying.

Some courtesy docks have an automated payment system, similar to a parking meter, that may charge a few dollars per hour stayed.

The downside of courtesy docks is that, while they are free and in great locations, they are usually in areas of downtown with high foot traffic and little – or non-existent – physical security (besides a CCTV camera and an occasional police drive-by). The public will be able to walk directly up to the side of your yacht. Some cruisers enjoy this, as it is common to be frequently engaged in conversation with passers-by; but some cruisers find the crowds too rowdy – after all, these docks are often in the center of town where restaurants, bars, and shops are open late into the night.

Another downside of courtesy docks is that they usually have minimal auxiliary services such as showers, toilets, or water. Power is sometimes available, but prior arrangements may have to be made to have the bollard unlocked or turned on.

And, as usual, always lock your yacht and secure everything on deck and down below, even if you are staying overnight in the boat.

Can my yacht do the ICW? Or even The Great Loop?

There are height and draught restrictions on the route.

Most bridges lift or otherwise open. Fixed bridges are typically regulated at 55ft or 65ft above high water. Bridge clearance is indicated on the charts. Also, bridge clearance is indicated on a water-level board at the base of the bridge, which is referred to as the “official” clearance. However, the bridges near Chicago are quite short – one bridge is 19ft 8in and does not open. In Chicago, it is possible to unstep the mast, pack up all the rigging, and ship it overland by truck to Mobile, Alabama (the end of the river journey for most vessels).

Most sailboats cruise the inland river systems as a powerboat. It is also possible to make arrangements to have a “stump” mast fitted so that VHF aerials, radomes, and anchor lights can still be mounted properly and only have 10-12ft clearance.

The official maintained the depth of the ICW and inland navigable waterways is supposed to be nine to twelve feet. Due to the enormous length of the coastline and inland rivers, this is not always possible. Coastal areas change more frequently than rivers, but areas near deltas, estuaries, or inlets should be traversed carefully. There are areas (particularly in Georgia and the Carolinas) that see 6ft draught at best. Hell Gate, south of Savannah, or the Dismal Swamp in North Carolina, are two of these areas. The locks and unusual canal regulation systems of New York and Canada may pose some limitations as well. Research these areas keeping in mind your yacht’s specifications prior to arrival.

Cruising the ICW and the Great Loop can be done with almost any normal vessel. Most cruisers from Europe, however, will be in a 40-45ft sailboat with a 60ft mast. This kind of sailboat is perfectly capable of making the journey with a few restrictions.

Using a Dinghy on the ICW

Whilst international cruisers visiting the USA will likely have their own dinghy or tender, it is not always a requirement for cruising in this area of the world. Due to the prevalence of dockage – free docks or otherwise – many cruisers report that they go multiple weeks on the ICW without putting the dinghy in the water at all.

Cruiser’s experiences vary, of course. Some prefer to spend most nights at Anchorage; some prefer to spend most nights in marinas – there is no “perfect” way to cruise the ICW. Those who anchor out will often still find that they only use their dinghies for recreation, for exploring, or for purposefully not going into marinas for budget reasons rather than by necessity.

One of the common uses for dinghies on the ICW is as an assist vessel in case of running aground (i.e., pulling the larger vessel or hauling an anchor). Another common practice if cruising with a dog is to anchor and use the tender to go ashore for walks.

Keep in mind that some of the ICW are inaccessible, even by dinghy, because it is either private property, or it may be marshland, rocky, or too steep.

Useful Links:

- Waterways Guide: https://www.waterwayguide.com/

- Captain John’s Great Loop Cruising: http://www.captainjohn.org/

- Great Loop Cruising Association: https://www.greatloop.org/

- Intracoastal Waterway Guide & Schedules etc.: http://www.offshoreblue.com/cruising/index.php

- Free docks located on the AICW: https://www.icwfreedocks.com/

- The Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway Association: https://atlanticintracoastal.org/

Notices to Mariners and news about shallows, obstructions and things to do with the Army Corps of Engineers. - Salty Southeast Cruisers’ Net app (for Android and for iPhones)

Cruising and navigation updates from a highly-regarded source. For both Android and iPhone on tablets or phones. - Tablet Navigation on the ICW (Tom Hale for PropTalk): https://www.proptalk.com/tablet-navigation-intracoastal-waterway-icw

Associated Reports & News

Noonsite:

- USA, Erie Canal: Transiting an Historic Waterway (SV Begonia – 2022)

- USA, Florida, Ft. Lauderdale: Plans to dredge the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) – (2014)

- Crossing Canada and voyaging down the St. Lawrence to Nova Scotia – (2011)

- From the Chesapeake to Lake Ontario, via the Hudson River – (2008)

External:

- Ten Tips for Navigating the ICW (AquaMap September 2024)

- Sailing America’s Great Loop on a Small Boat (Cruising World June 2023)

- 10 Reasons to Sail the Intra Coastal Waterway (Sailing Britican)

- Why Would Anyone Want to Cruise the Great Loop? (Commuter Cruiser, Nov 2017)

- Georgia on My Mind: Cruising Coastal Georgia and the Low Country (Cruising World, Oct 2017)

- Cruising Through America: Chicago to Mobile (Quantum Sails, March 2017)

- Middle Earth on the ICW – Georgia’s Cumberland Island (Cruising World, April 2016)

- The Hatteras Bypass (Cruising World, Sept 2015)

Publications:

- Atlantic to Great Lakes – Choosing your Great Loop route (The Waterway Guide)

- Waterway Guide: Atlantic ICW (Paradise Cay Publications)

- The Intracoastal Waterway – Norfolk to Miami

- 2017 Atlantic ICW Cruising Guide

Related to following destinations: Canada, Nova Scotia, Ontario, USA

Related to the following Cruising Resources: Cruising Information

If you plan to travel the ICW you will find it very rewarding, but some areas can be a challenge without local knowledge. There is generally plenty of water in the ICW even at low tide, but the trick is finding it. Charts of the ICW historically showed a center line, or as it was called the Magenta Line, based on the color. Even though you will still see the Magenta Line on some chart areas it does not necessarily mark the deepest water.

Thanks to the efforts of a gentleman who travels the ICW twice a year we now have a source for tracks showing the deepest water in all the Atlantic ICW. Robert Sherer, or better known as Bob423, shares his tracks and makes them available for download to your favorite navigation app or chartplotter. Just visit his website https://bobicw.blogspot.com/p/bob423-long-tracks.html and follow the instructions. You can also follow Bob423 and ask questions on his Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/groups/ICWCruisingGuide

Already listed in Useful Links above are Waterway Guide and Cruisers Net. Both are excellent sources for information and have apps for use on your favorite phone or tablet. If free docks are your thing, then also listed is an online guide to ICW Free Docks at https://www.icwfreedocks.com/. I publish this guide and make it available at no cost for users. If you have any questions, there is a contact form on the website. You can also message or discuss free docks on my Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/icwfree. I will try to answer your questions or point you in a direction for help.

Thanks so much for this great feedback!

Posted on behalf of Bill Willmann, S/V VIVA:

I’m planing to do the Great Loop in 2018 and am in the process of collecting all the information I can. Your article emphasizes the rules, laws, and regulations and makes it sound like a cruiser will be dealing with authorities day and night. An international cruiser (17 years), I did the ICW a few years ago from the Florida Keys to the top of the Chesapeake and back. It took five or six months, and albeit that I’m a courteous and experienced cruiser and fly an American flag, I was only stopped once by the authorities, and that was to ask for proof of dinghy ownership because a similar one had been lost/stolen in the area.

I understand you have to prepare your readers for what could happen, but my fear is that your article will unnecessarily discourage sailors, especially non-Americans, from seeing the real America and learning that we aren’t what they see on the news, etc. Every European I’ve met who has ICW and/or Loop experience has had a very positive, glowing experience, in awe of the navigational aids and friendliness and helpfulness of the people, including the authorities.

Thank you for Noonsite – it’s a great resource for all of us.

Nov 2018

We motored down the ICW from Hampton, Virginia to Charleston South Carolina, we popped out at Beaufort and back in at Georgetown. Then we continued on the ICW until Charleston.

We didn’t have any problems with our draft of 5 ft (1.52M) and our mast height of 55 ft (16.76M) and although there was debris, we managed to avoid it. I also joined a Facebook group called “ICW Cruising Guide by Bob423”. It’s run by Bob Sherer. You can check our website for our route: http://www.untilthebuttermelts.com

Please remember that flood waters from Florence and now from Michael will have lifted tons of debris into the Waterway channels and submerged hazards can do serious damage to your vessel. See Waterway Guide for the latest updates – https://www.waterwayguide.com.