INSIGHTS: Boatschooling – Ages 4 to 12

Author Kate Laird has sailed with her husband and children aboard their yacht SEAL since 2004, from Greenland to Antarctica to Alaska. She has home-schooled her children on board throughout their school years. Here she allays some of the fears that first-time boat schooling parents feel and answers all those questions you’ve been wanting to ask if educating your children on board is on the cards.

Published 4 years ago

Are you excited by the dream of long-term cruising, but horrified at the thought of taking responsibility for your children’s educations? Do you have preschoolers on board, but you’re heading back to land because you can’t imagine teaching them to read? Are you rushing to finish your trip around the world in order to be back at school for middle school or high school?

- Helen and Anna Laird, ages 4 and 2 in the dinghy in Belize.

My children have lived on board the boat since they were two and four, and they’ve homeschooled all the way through. The elder left for Dartmouth last August and has now returned to the boat to finish up her first year online during the pandemic. The younger has just finished high school on board and will start Yale in a few weeks. One is planning to major in biology, the other in history.

You can homeschool your children on board a boat in the middle of nowhere.

This first INSIGHTS will cover children aged 4-12; I’ll cover ages 12-18 in the next in the series.

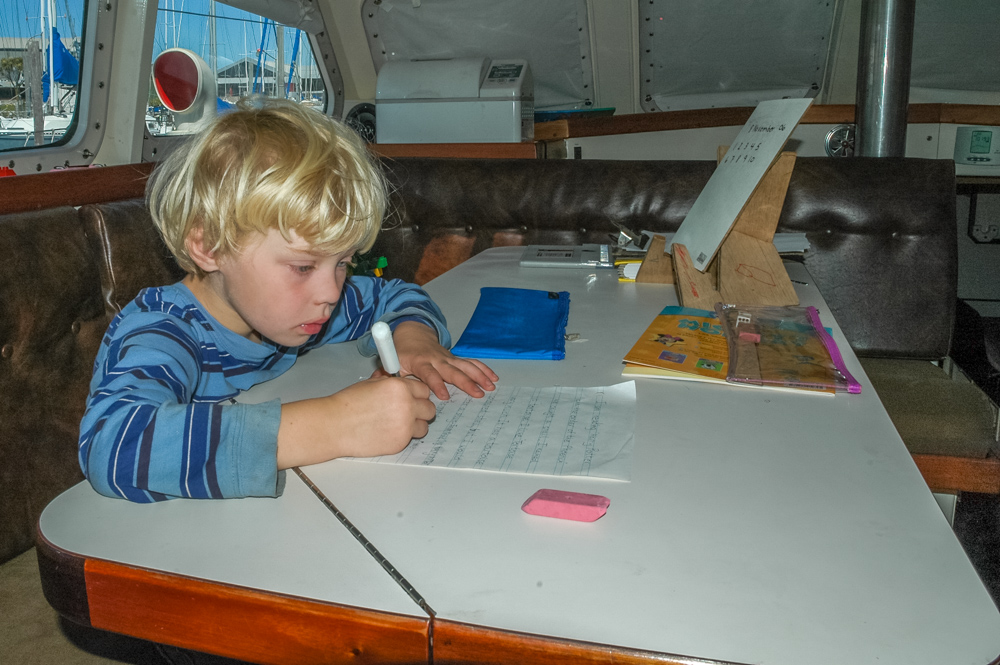

- Helen and Anna Laird, ages 5 and 3 working on school in their cabin. Helen was beginning to learn to read at this stage; Anna had a preschool workbook to doodle in at the same time, which she did if she wanted to keep her sister company.

Is it legal?

The first question is a legal one: where do you “live” officially, and can you homeschool? It is legal in many countries, illegal in others, but I have never heard of sailors encountering legal difficulties in homeschooling their children while in foreign ports. Legality in your home country is another matter. Residency can be a tricky question for homeschoolers, just as it is for other aspects of cruising – where do you renew your driver’s license? What is your address for health insurance? What is your tax address? Your voting address?

Some countries make it very easy – France offers CNED, a complete program that keeps students exactly in line with their peers in school. New Zealand offers homeschooling for travelers for a few years. Australia does as well. Homeschooling is not allowed in Germany and Austria, so Austrian families sometimes use German books and German families use Austrian books to stay under the radar. Each US state has its own rules and different levels of reporting requirements.

Some countries welcome cruising families joining their schools for a few months. In some countries it is illegal and can lead to deportation.

Should you buy an all-in-one curriculum?

If you are French, you should probably use CNED. It’s likely the reason most of the sailing families we’ve met are French – there’s much less downside or perceived risk to homeschooling, because they will send you everything you need in a box, and you know your children will have no problem fitting into school when, and if, you return to France.

If you aren’t French, the answer is maybe. Many countries have similar programs, and they can be a great option if you are planning to return your children to public school in your home country after a set number of years.

Should you use a mix and match approach?

Most children are a little ahead in some subjects and a little behind in others, and it is often easier to shop for programs in individual subjects. If you’re doing it this way, you can also design classes yourself, or design some and buy others. You can also blend styles of homeschooling, using a “sit at the table and do the worksheet” approach in some subjects and a “wander outdoors and learn from the world” approach in others.

- Anna age 6 learning to read in Chile.

Can your child read?

Reading is step one. Don’t worry about adding in lots of other subjects when you begin school. Handwriting may reinforce reading for some children, but it may confuse matters for others. Don’t be afraid to try it, but back off if it’s not helping with reading.

- Helen age 6 working on handwriting in Argentina.

Children are ready to learn to read between the ages of 4 to 8. Can you think of another children’s milestone that has such a wide range? Some children will just “pick it up” from sitting on your lap while you read to them. Most won’t.

Languages vary enormously in how hard it is for native speakers to learn to read. Languages such as English, French, Arabic, Chinese, and Japanese are very difficult because there are so many different ways to write each sound. Italian, Finnish, and Turkish are much more straightforward. Spanish, German, and Russian are somewhere in between. The more ways there are to spell each sound, the harder it is to learn to read.

Most children benefit from methodical instruction. Most parents benefit from scripted programs. (Classroom teachers generally hate scripted programs, but they are facing an entirely different task teaching dozens of children at one time.)

In English, I recommend All About Reading as a program designed for home instruction that teaches reading in a methodical, scripted way. If that is too expensive, I recommend Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons. These both use American spelling, but that has presented no problem for my English/American children.

When you start teaching reading, don’t be afraid to quit for a couple of months if it isn’t going well. If your child doesn’t read at an average level by age eight, consider doing testing for dyslexia or other learning disabilities. You can test reading levels with a leveled reading workbook. (I don’t recommend doing the worksheets in these books, but they are useful in providing leveled text samples.)

How long will you be away from schools?

Are you planning on setting sail for a single year? Five? Twenty? That makes a huge difference in what sort of school you need to have. If you’re only traveling for a single year, you can cut down to reading, math, and writing, and your children will be ready to re-join their peers in the next school year. Any loss of history, science, and second language study will be made up for seeing the world around them, visiting other ports, and learning about the oceans, the wildlife, and the stars.

- We found some owl pellets on a walk – Anna and Helen age 4 and 6 dissected them to find mouse bones inside.

If you’re planning on homeschooling for several years – or every year – you will need to consider more subjects. However, it is possible to be flexible with the way you teach those subjects. You can have a light school during part of the year and increase intensity when you are not making ocean passages. You can teach some subjects and unschool others. Unschooling means learning without sit down worksheets or planned lessons. Unschoolers usually “strew” information around – they buy lots of educational books and media, but let the students choose what they will learn.

- School can be formal “lessons” like this Spanish class at the saloon table, or it can be found outdoors in the wild….

- like this photo of Anna age 4 with a scapula.

For us, my motto was “Unschool when you can, teach when you must.” In elementary school, I taught the technical side of reading, handwriting, math, and history (which included writing). My children unschooled literature and science. I provided great books and audio books. I provided lots of science equipment, nature books, and 50,000 miles of ocean sailing from the Arctic to the Antarctic.

- Helen and Anna practicing penmanship and helping with provisioning.

Although we covered a lot of miles in early elementary school, we tended to have six months of constant movement (and charter guests) and six months of slow travel. I didn’t try to have school in the charter season, and six months a year was plenty of time to get through elementary school.

- More natural history – Anna and Kate whale watching in Antarctica

For two years, we were more typical cruisers, and sailed through the South Pacific and New Zealand, with lots of passages interspersed with slower cruising life. Those years, we had school “every day” except on passages or when there was something more interesting to do. We ended up with about the same number of school days as our six-month school years, and we covered a 9-month school year’s worth of material in 12 months.

How do you choose materials?

These days, there is almost too much choice, particularly in English. However, many of the English-language materials are aimed at religious homeschoolers. It is important to avoid faith-based materials in science and history if you would like your child to study at an academically-oriented school or university in the future, and it’s worth being aware that faith-based materials often imbue literature and math programs with more religious messaging than you might want, even if you are religious.

Curriculum materials are often labeled as “faith-based,” “neutral,” and “secular.” Neutral materials are designed to meet the needs of both faith and secular homeschoolers, but they are generally inadequate in science because they often skip over many topics, including evolution, climate change, geological change and the Big Bang. Neutral and faith-based history programs often privilege a particular religion. Secular history programs do study religion, but as a historical topic, rather than a truth.

English-speaking sailors used to rely on the secular Calvert program, which came in a box per year for ages 5-14. A “neutral” company recently bought the name and moved it to all online instruction and is therefore no longer an option for most sailors. I wrote a blog last year called “No Calvert? No Problem” with suggestions for combining existing subject-area secular curriculum into a complete school.

English speakers may also find seahomeschoolers.com helpful. They have one of the tightest secular definitions, and so you can be confident that any materials recommended on that site or in their Facebook Group are appropriate for academically-based learning.

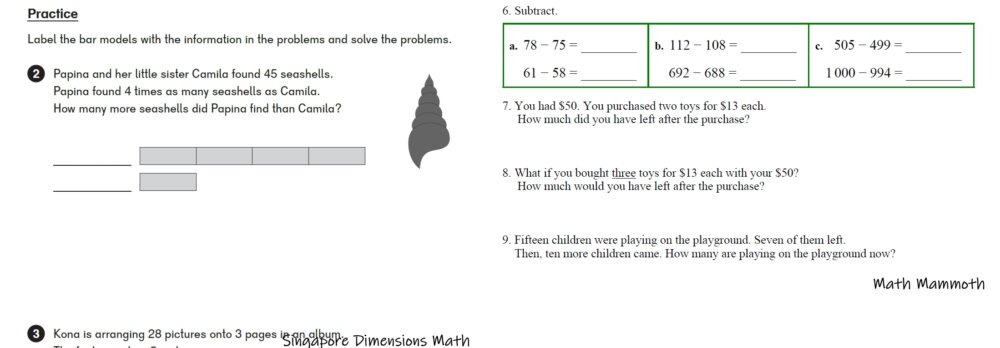

Most young students do better with math programs that come in workbooks, where they write directly on the same page as the problems. Around age 12, this becomes less of an issue, and most students can move to a textbook or computer screen and a separate notebook. Some students will find this transition hard and may seem to have math difficulties, when in fact they are having trouble with reading and writing. Almost all students will do better if they are writing out their mathematics work on paper rather than doing it on a screen. It may be hard to convince them of this, however.

- Singapore Dimensions Math and Math Mammoth – the math concept is harder on the left-hand Singapore Math workpage, but it will be relatively easier for most students because of the pictorial element and more space to do the work. In math it’s important to pay attention to layout and space for working. Some students do very well with the more cramped Math Mammoth pages on the right, but some do not – it is a question of visual maturity, not math ability.

Fixed school time or a more relaxed approach?

In elementary school, almost every moment of school needed supervision and encouragement, so we had school every morning, more or less from eight until noon. Most boat kids follow a similar schedule. In middle school, it took a bit longer, but since literature was entirely unschooled, they fit that in at other times of the day. I felt they should read for pleasure for a minimum of thirty hours a month, but I didn’t care if that was in chunks of five hours or an hour a day. For most boat kids, that is an easy goal to meet. We met only one boat child who never chose to read, and this was unusual enough that her parents chose to have her professionally evaluated; she was profoundly dyslexic and needed targeted teaching to overcome it. (This particular family was heading to shore anyway, so she developed her reading skills in school, but many families successfully homeschool children with learning difficulties.)

It can be helpful for parents to negotiate how rigidly they will adhere to school hours, so as to provide a united front. Is school M-F, 8-12, no matter what? Or do opportunities for snorkeling, fishing, visiting ashore take priority? We found it useful to have school 7 days a week, which meant that if there were interesting things to do, we could take a day off whenever we felt like it.

Who is the teacher?

Every family has a different approach. In our case, I was the sole teacher. On other boats parents shared the job completely, or specialized in different subjects, or alternated every couple of months. On many boats, the mother was the sole teacher; on others it was the father’s job. Some boats take tutors with them – this is how I got my start in homeschooling and ocean sailing when I was 22.

Motivation

In our family, we handled motivation by being boringly consistent. For the first few years, school was non-negotiable. (This firmness was made easier and more important by our six month on/six month off schedule.) By middle school, they were used to the idea of homeschool, so if we took a couple of days off to have fun or make a passage, they could slot right back into school. It seems that the first couple of years are hard going, no matter how old the children are.

Up until age 12, I found that if they were not doing the work, the problem could usually be solved by my stepping in and looking over their shoulders. I was extremely careful not to threaten punishments that I wasn’t willing to follow through with or that would actually punish me instead. (I did this once – I kept our younger daughter on board in the afternoon to finish her school work, while my husband Hamish took the elder for a trip to town. It was a good lesson for me: my daughter didn’t care about staying on the boat, and I did!)

What equipment do I need?

Printer: We homeschooled ages 5 to 10 without a printer. Then we purchased a portable ink jet and spent vast amounts of money on ink and getting ink pots refilled in different countries. Finally, when the kids were 12 and 11, we bought a black and white laser printer, which has been invaluable for printing pdfs, papers, and everything else. It is a power hog – we need a very sunny day or the engine running in order to power it. With the ink jet, we could do it off the batteries.

Notebooks and Lined Paper for handwriting practice: We used a lot of spiral bound notebooks in primary school because it meant there weren’t any loose pages flying around. For early handwriting practice I bought age-appropriate special paper, but I could have also printed these if we’d had a laser printer.

Art Supplies: Endless. We started with low-priced artists’ sketch pads because the thicker paper was better for young kids. In the middle years, they used printer paper for everything, and now in high school they use higher quality sketch pads and printer paper. I couldn’t handle the mess of paints, so they started with washable markers, moved to pencil, and then started painting in high school. Your patience may be greater than mine. Most boat kids love drawing.

Math manipulatives: Most primary school students learn math better using manipulatives. Poker chips are the cheapest option, and there are all sorts of rods and base ten blocks and other tools that make understanding math easier. Older children (age 10 and over) will find tools useful – protractors, rulers, compass, and so on. Depending on your math program, a calculator may be helpful. We did not use calculators until high school (secondary school) math.

Laptop/tablet with keyboard: At about age 9 or 10, it’s a good idea to start using a keyboard if you haven’t done so already. Some people may have already purchased devices for their children, others are trying to avoid screen time. Touch typing may help children with spelling difficulties because it’s a muscle-memory task rather than a handwriting task.

Science equipment: Magnifying glasses, a rectangular plastic fish tank, a 12 volt fish tank aerator, binoculars, bird and sealife identification guides all help you do nature studies in early primary school.

Microscope: After age 10 or so, a microscope may be a wonderful addition. There are two types – dissection (stereoscope) microscopes that let you look at large three dimensional things (flies, for example, or fish scales), and cellular (compound) microscopes that let you look at tiny things like cells and the detail on a fish scale. Even when the two types of microscopes are at the same magnification (the highest magnification on a stereoscope microscope is often the lowest level on a compound microscope), the stereoscope will have a better depth of field than the compound.

A cheap compound microscope can be a good field microscope and handle abuse, but it will likely mean buying a second compound microscope for high school work. A high-quality high school one will likely be too fragile for the manhandling of under 11-year-olds.

Another solution is to buy the high school one early and buy one with a usb hook up for a computer, or rig a camera over the microscope and feed that to the computer. That way, younger children can see what’s in the microscope without actually touching it. It’s also a good solution for keen high school scientists: buying a single eye piece compound microscope is a lot cheaper than a dual eye piece scope, but it’s uncomfortable for long stretches of work. Moving the work to the computer screen solves that problem.

- Helen checking out a broken piece of electronics in the stereoscope microscope

In Conclusion

Had we only been leaving schools for a year, I would have focused on math, reading, writing, and seeing the world. Because we were on the boat for all fifteen years of their pre-university educations, however, I had to make sure we covered everything and that meant treating teaching as a job. Helen and Anna didn’t enjoy every minute of it, to be sure. We had good days and bad days, but by following unschool when you can, teach when you must, I was able to reduce their school time to the minimum amount of time. This left them plenty of time to play outdoors and see the world – and to fall in love with literature and education on their own terms.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Kate Laird graduated from Harvard with a degree in history, a 100-ton captain’s license, and a severe case of wanderlust. Her first teaching job began seven days after graduation, tutoring three children on a sailboat crossing the Pacific. That “year off” turned into thirty, as she worked on boats around the world, sometimes pausing to write about it.

In the middle, she taught for another two years at the University of New Hampshire, while earning an MA in English, but then didn’t think much more about education until it came time to teach her two daughters. The last fifteen winters have been devoted to their educations, as the family have worked and traveled on the edges of civilization.

In the summers, Kate with her husband Hamish, run expedition charters and remote cruising workshops for adventurers, scientists, and mountaineers. After many years in Antarctica and South Georgia, they came to Alaska in 2013. They have used this past season to find new routes and anchorages, and look forward to the start of next charter season. Both daughters are now off at university, at Yale and Dartmouth, one majoring in biology, the other in history.

Kate’s book, Homeschool Teacher: A Practical Guide to Inspiring Academic

Excellence, is available in both paperback and Kindle formats at Amazon or via http://katelairdbooks.com.

More information about Kate and Hamish Laird, and their expedition charter boat Seal can be found at https://expeditionsail.com.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Related Links:

- Homeschool Teacher: A practical guide to inspiring academic excellence – by Kate Laird

- More Insights can be found here.

- Family adventure: How we home-schooled our kids while sailing across the Pacific (Yachting World – September 17, 2020)

- Cruising with Children – Noonsite page

- Maybe the Best Home School Is … on a Boat? (NY Times – Sep, 2020)

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of Noonsite.com or World Cruising Club.

Related to the following Cruising Resources: Cruising Information, Cruising with Children, Insights, Planning and Preparation

This is a great, helpful post. Thank you for sharing. We have just purchased Kate’s book.