Weather: From La Niña to El Niño

Just as scientists are calling the end of a La Niña weather cycle, they are now on El Niño Watch, which means that conditions are favorable for the development of El Niño conditions within the next six months.

Published 2 years ago

According to a senior research scientist at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), El Niños typically come about once every four years or so.

“We’re due one,” NOAA’s Dr. Mike McPhaden said. “However, the magnitude of the predicted El Niños shows a very large spread, everything from blockbuster to wimp.”

While it’s normal for regular El Niño events to occur every few years, it’s abnormal to have extreme ones so close together. Those large events are more of a once every 15-20 years thing. Since the last big one was in 2015-2016, another one this year would be “very unusual,” according to Dr. McPhaden.

Be watchful and be prepared

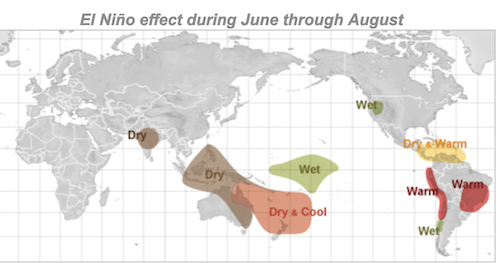

“The really big ones reverberate all over the planet with extreme droughts, floods, heatwaves, and storms,” Dr. McPhaden warned. “If it happens, we’ll need to buckle up. It could also fizzle out. We should be watchful and prepared either way.”

What are El Niño and La Niña? – Source NOAA

El Niño and La Niña are opposite phases of a natural climate pattern across the tropical Pacific Ocean that swings back and forth every 3-7 years on average. Together, they are called ENSO (pronounced “en-so”), which is short for El Niño-Southern Oscillation.

The ENSO pattern in the tropical Pacific can be in one of three states: El Niño, Neutral, or La Niña. El Niño (the warm phase) and La Niña (the cool phase) lead to significant differences from the average ocean temperatures, winds, surface pressure, and rainfall across parts of the tropical Pacific. Neutral indicates that conditions are near their long-term average.

Typical of La Niña summers, higher-than-normal air pressure was observed to the east and south of New Zealand, with lower-than-normal air pressure to the north and west.

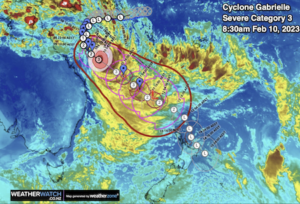

Impacts for Hurricanes and Cyclones

According to NOAA, the continental United States and Caribbean Islands have a substantially decreased chance of experiencing a hurricane during El Niño and an increased chance of experiencing a hurricane during La Niña.

Overall, El Niño contributes to more eastern and central Pacific hurricanes and fewer Atlantic hurricanes while, conversely, La Niña contributes to fewer eastern and central Pacific hurricanes and more Atlantic hurricanes..

Pacific countries also on El Niño watch

In the Pacific, Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) is also on El Niño watch. According to the BOM website, the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is currently neutral (neither La Niña nor El Niño). Oceanic and atmospheric indicators for the tropical Pacific Ocean are at neutral ENSO levels.

However, there are some signs El Niño may form later in the year. Therefore, the ENSO Outlook is at El Niño WATCH. This means there is approximately a 50% chance of El Niño in 2023.

International climate models suggest neutral ENSO conditions are most likely to persist through autumn. From July, all but one of the models indicate El Niño thresholds will be met or exceeded, with all models by August. Current ENSO outlooks extending beyond autumn should be viewed with some caution as they typically have lower forecast accuracy than forecasts made during other times of the year.

When ENSO is neutral, the Pacific Ocean typically exerts little influence on Australian climate patterns. El Niño typically suppresses rainfall in eastern Australia during the winter and spring months.

Pacific wind conditions

The winds near the surface in the tropical Pacific usually blow from east to west. For reasons scientists don’t yet fully understand, these relatively steady winds sometimes weaken or strengthen for weeks or months in a row. Weak winds allow warm surface waters to build up in the eastern Pacific. Sometimes, but not always, the atmosphere responds to this warming with increased rising air motion and above-average rainfall in the eastern Pacific. This coordinated change in both ocean temperatures and the atmosphere begins an El Niño event. As the event develops, the warmed waters cause the winds to weaken even further, which can cause the waters to warm even more.

New Zealand’s NIWA sees El Nino later in the year

New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) saw La Niña ending during March, concluding its three-year run. A dramatic change in tropical trade winds resulted in warming seas across the equatorial Pacific. As of late March, ENSO-neutral conditions were occurring, but El Niño conditions may arrive as early as winter. An El Niño Watch has been issued to cover this potential.

NIWA’s analysis indicates that La Niña conditions will transition to ENSO-neutral during March-May, most likely during March (95% chance). During June-August, El Niño is favoured at around a 60% chance. The chance for El Niño remains around 60% from September-December 2023. The potential for El Niño conditions by the end of the year is also supported by trends in sub-surface ocean conditions and trade winds.

…………………………

Related News:

- ENSO Update -El Niño Watch – NOAA

- Climate Driver Update – Australia Bureau of Metereology

- El Nino – Seasonal Climate Outlook – NIWA – New Zealand

…………………………

Related Links:

- National Weather Service – Climate Prediction Center

- Frequently Asked Questions about El Niño and La Niña (NOAA)

- NIWA – New Zealand

- Weather Impacts of ENSO – Weather.Gov

………………………………

Noonsite has not independently verified this information.

………………………………

Find out all news, reports, links and comments posted on Noonsite, plus cruising information from around the world, by subscribing to our FREE monthly newsletter. Go to https://www.noonsite.com/newsletter/.

Related to following destinations: Aiwo, Alofi, American Samoa, Australia, Australs, Christmas Island/Kiritimati, Clipperton Atoll, Cook Islands, Fiji, French Polynesia, Gambiers, Gilbert Islands, Kiribati, Line Islands, Marquesas, Nauru, New Zealand, Niue, North Island (New Zealand), Northern Group (Cook Islands), Other Atolls (French Polynesia), Phoenix Islands, Samoa, Society Islands, South Island (New Zealand), Southern Cook Islands, Tahiti, Tonga, Tuamotus, Western Samoa

Related to the following Cruising Resources: Atlantic Crossing, Caribbean Sea, Circumnavigation, Forecast Services, Hurricanes and Tropical Cyclones, Pacific Crossing, Pacific Ocean East, Pacific Ocean South, Routing, Weather